Hundreds of new products using nanotechnology emerging

August 4, 2009

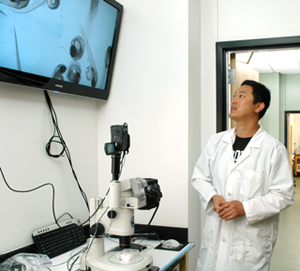

Shosaku Kashiwada

Shosaku Kashiwada

Dr. Shosaku Kashiwada is like most scientists – proud to see his research cited in print, particularly in a prestigious scientific journal that generates applause from friends and colleagues.

That’s probably why he was a bit surprised by the reference that appeared on the Internet in April – not from a peer-reviewed scientific journal – but on Nanolawreport, a newsletter published by a well-connected Washington law firm.

Turns out that the lawyers are looking over Kashiwada’s shoulder as he investigates some of the negative consequences of nanotechnology, the manipulation of matter at the nanoscale or “one billionth” of a meter. That’s about one millionth the diameter of a human hair.

“Nanotechnology is one of the three pre-eminent environmental law issues,” said Roger Martella, former U.S. EPA general counsel, in a recent story in NanoWerk, a web portal devoted to nanotechnology and nanosciences.

Kashiwada, a research assistant professor in the Arnold School’s Department of Environmental Health Sciences, draws inspiration for his work from the late biologist Rachel Carson, whose 1962 book Silent Spring is credited with starting the environmental movement in the U.S.

Carson spent four years documenting the harmful environmental impact of DDT which had been widely used as a pesticide beginning in World War II. One outcome of that effort was the banning of DDT by the U.S. government in 1972.

Kashiwada and many other scientists see similar potential dangers in unmonitored use of nanotechnology which is increasingly being used to create new materials and devices with wide-ranging applications.

Some recent applications of nanotechnology include nanocomposites incorporated in car bumpers that are 60 percent lighter and twice as resistant to denting and scratching, nanoparticles embedded in cloth to create stain-repellent khakis, nanoscale photophosphors in LCD panels, additives to orange juice and milk to enhance “pourability”, and as antimicrobial wound dressings using silver nanocrystals that kill many germs.

Kashiwada says global spending on nanotechnology research and development is some $9 billion annually and growing rapidly.

A year ago, the Project on Emerging Nanotechnologies estimated that more than 800 manufacturer-identified nanotech products were publicly available, with new ones hitting the market at a pace of 3-4 per week.

Manufacturing of nanomaterials and the consumer use of products that contain them will inevitably lead to “a new class of environmental damage, but only $36.5 million is currently being spent on studies targeted at understanding the effects of nanoparticles on human health and the environment in the U.S. and European Union,” said Kashiwada.

Examination of the consequences of nanotechnology promises to be a good niche for USC researchers such as Kashiwada, said Arnold School Dean Dr. Tom Chandler.

“Shouldn’t society have some precautionary principles in place before we start making all these products using nanoparticles? The Environmental Protection Agency and the National Science Foundation are definitely interested in exploring that issue.”

“The EPA realizes the nanotechnology industry is growing exponentially and they don’t want to get caught unprepared for any unintended human health or environmental consequences,” Chandler said.

In the study that caught the attention of the law blog, Kashiwada reported on his continuing work on the impact of water-suspended fluorescent nanoparticles on a species of small fish and their hatchlings.

Kashiwada set up a series of experiments in his fourth floor laboratory in the Arnold School’s Public Health Research Center. The test subjects were hundreds of Medaka fish including a see-through type, a strain of fish that has no pigment so its internal structures are visible to the naked eye. These fish are a widely used substitute for human health studies because they share many of the same genetic, molecular and physiological systems common in humans and other vertebrates.

Kashiwada exposed the fish and their offspring to nanospheres in various sizes and at various water salinity levels.

After analyzing the results, Kashiwada concluded that nanoparticles entered the Medaka through the membrane of the gills and intestine, then entered the bloodstream and were transported and deposited into various organs.

The Medaka demonstrated no harmful effects from low levels of exposure to the nanospheres but died when the water salinity was increased concurrent with exposure. Kashiwada concluded that “salinity may affect the ability of nanoparticles to penetrate cell membranes and tissues.”

In addition, Kashiwada demonstrated multiple biological effects caused by silver nanocolloids, which have been used for commercial products in the healthcare sector. He found silver nanocolloids inhibited normal development of medaka embryos and that this inhibition was caused at environmentally realistic concentration levels. Now, Kashiwada is moving his research to evaluating gold nanoparticles because gold nanoparticles are a very promising material for medical uses, and many scientistists assume they are safe and benign.

He also cautioned that “until more is known about the environmental and human health effects of nanomaterials, the release of manufactured nanomaterials into the environment should be avoided as far as possible.”

Kashiwada has been on the ENHS faculty for three years, developing close research collaborations with Chandler, Dr. Tara Sabo-Atwood, an assistant professor in the USC Department of Environmental Health Sciences, and Dr. Lee Ferguson, an associate professor in the USC Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry.

_01.jpg)

_02.jpg)